Anti-HBe (Anti-Hepatitis B e-antigen)

Useful For

The appearance of antibodies to Hepatitis B “e” antigen is an indicator of resolution of acute infection, used to monitor treatment.

Testing Algorithm

| Reporting Name | Available separately | Always performed |

| Anti-HBe | YES | YES |

Indications for Testing

· Staging of chronic infection

· Monitoring response to therapy

HBeAg should be ordered by hepatitis specialists to stage chronic hepatitis B infection and/or monitoring treatment response (see Special Instructions).

Clinical Information

HBeAg is first detectable in the early phase of hepatitis B viral infection, after the appearance of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), or consistently during or after a burst in viral replication. The titers of both antigens rise rapidly during the period of viral replication in acute infection. Spontaneous conversion from e antigen to e antibody (a change known as seroconversion) is a predictor of long-term clearance of HBV in patients undergoing antiviral therapy and indicates lower levels of HBV and therefore lower infectivity. A negative HBeAg result may indicate (1) early acute infection before the peak of viral replication or (2) early convalescence when HBeAg has declined below detectable levels. The presence of anti-HBe serves to distinguish between these two phases. A subset of chronic hepatitis B patients have no detectable HBeAg in serum, but are positive for anti-HBe; these patients may also be positive for serum hepatitis B virus DNA. Additionally HBe antigen/antibody seroconversion is used as an indicator of virological response when treating patients with chronic hepatitis B.

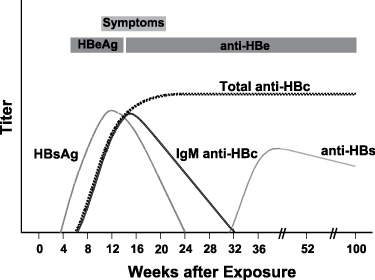

Typical sequence of serologic markers in patients with acute HBV infection with resolution of symptoms (Horvat, R. T., and Tegtmeier, G. E. 2007).

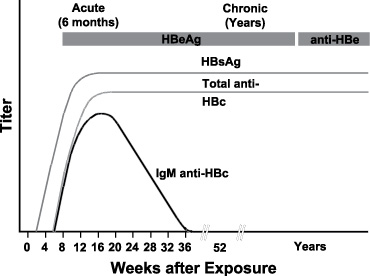

Typical sequence of serologic markers in patients with HBV infection that progresses to chronicity. In patients with chronic HBV infection, both HBsAg and IgG anti-HBc remain persistently detectable, generally for life. HBeAg is variably present in these patients (Horvat, R. T., and Tegtmeier, G. E. 2007).

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) causes a wide spectrum of manifestations ranging from asymptomatic seroconversion, sub-acute illness with non-specific symptoms (e.g. anorexia, nausea, or malaise) or extrahepatic symptoms, and clinical hepatitis with jaundice, to fuliminant fatal hepatitis. Only 10% of children and 50% of adults will exhibit symptoms. An acute illness may last up to three months with a fatality of 1-2%. In most acute cases HBsAg serum levels are positive initially, resolve and the individual develops anti-HBs which confers immunity.

HBV occurs worldwide, and is endemic in some Asian countries. In Canada the incidence of acute hepatitis B is estimated to be 2.3 per 100,000. In developed countries exposure to HBV may be common in certain high-risk groups such as injection drug users, person who have multiple sex partners, men who have sex with men, sex with HBV-infected persons and having a hepatitis B carrier in the family. The prevalence of chronic hepatitis B varies in different populations.

Chronic HBV infection is found in 0.5 % of adults in North America. After acute HBV infection, the risk of developing chronic infection varies with age; infants infected at birth have a 90% chance of becoming a chronic carrier. A chronic carrier is one who retains HBsAg positivity six months after the initial infection. These individuals are always infectious. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatic cirrhosis is likely to result in the premature death of 15-25% of those who have chronic HBV.

Reference Values

Interpretation

For diagnostic purposes, and to stage the disease, results should be used in conjunction with patient history and other hepatitis markers for diagnosis of acute or chronic infection (see special instructions).

REACTIVE:

A REACTIVE anti-HBe indicates early convalescence when HBeAg has declined below detectable levels.

NON-REACTIVE:

A NON-REACTIVE result may indicate early acute infection before the peak of viral replication.

See Special Instructions for PHL recommended diagnostic approach to hepatitis.

Clinical Reference

Curry, M. P., and Chopra, S. 2010. Acute Viral Hepatitis, p. 1577-1592. In Mandell, D., Bennett, J. E., and Dolin, R. Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 7th ed., vol. 2. Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA.

Horvat, R. T., and Tegtmeier, G. E. 2007. Hepatitis B and D Viruses, p. 1641-1659. In Murray, P. R., Baron, E. J., Jorgensen, J. H., Landry, M. L., and Pfaller, M. A. Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 9th ed., vol. 2. ASM Press, American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

James Koziel, M., and Thio, C. L. 2010. Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis Delta Virus, p. 2059-2086. In Mandell, D., Bennett, J. E., and Dolin, R. Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 7th ed., vol. 2. Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA.

Abbott. 2004. Architect System Anti-HBe: package insert. Abbott, Diagnostics Division. Wiesbaden, Germany.